OS 3.02 - Process Scheduling

The objective of multiprogramming is to ensure that some process is always running, maximizing CPU utilization.

The goal of time-sharing systems is to switch the CPU between processes frequently enough that the user can interact with each program while it is running.

To achieve these objectives, the Process Scheduler selects an available process from a set of processes waiting for execution on the CPU. When there are more processes than available CPU time, some processes must wait until the processor is free to be rescheduled.

3.2.1 Scheduling Queues

When a process enters the system, it is placed in the job queue, which consists of all the processes in the system.

Ready Queue:

The processes residing in main memory, ready to execute, are placed in the ready queue, which is generally implemented as a linked list.- The ready queue header contains pointers to the first and last PCBs (Process Control Blocks).

- Each PCB contains a pointer to the next PCB in the queue.

Device Queue:

If a process requests I/O (e.g., disk access) and the device is busy, the process is placed in the device queue for that specific I/O device. Each device has its own queue.

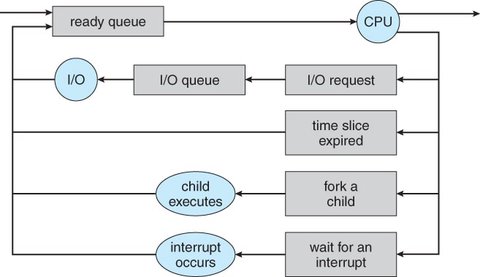

Process Lifecycle in Queues:

New Process:

- A process is initially placed in the ready queue.

- It waits there until it is selected for execution, or dispatched.

During Execution:

- The process may:

- Issue an I/O request and move to the I/O queue.

- Create a child process and wait for the child’s termination.

- Be removed forcibly from the CPU due to an interrupt and moved back to the ready queue.

- The process may:

Cycle Continuation:

- The process moves from the waiting state to the ready state when I/O or other events complete and is placed back into the ready queue.

- This cycle continues until the process is terminated, at which point it is removed from all queues, and its PCB and resources are deallocated.

3.2.2 Schedulers

A process moves between various scheduling queues throughout its lifetime, and the Operating System (OS) must select processes from these queues for execution.

Types of Schedulers:

Long-Term Scheduler (Job Scheduler):

- Selects processes from a pool and loads them into memory for execution.

- Controls the degree of multiprogramming (the number of processes in memory).

Short-Term Scheduler (CPU Scheduler):

- Selects from the ready queue and allocates CPU time to one of the processes.

- Frequency of execution: It is very fast as it must select a new process frequently due to the short time between executions.

Types of Processes:

I/O Bound Processes: Spend more time performing I/O operations than computations.

CPU Bound Processes: Perform infrequent I/O operations and spend more time on computations.

For better system performance, a combination of I/O-bound and CPU-bound processes should be selected (Process Mix).

Differences Between Long-Term and Short-Term Schedulers:

Short-Term Scheduler:

- Handles CPU-bound processes and performs scheduling frequently to ensure minimal wastage of CPU time.

Long-Term Scheduler:

- Manages the mix of CPU-bound and I/O-bound processes.

- A balance between these types ensures that the ready queue does not empty (if too many I/O-bound processes) and CPU scheduler will have nothing to do or the I/O waiting queues remain empty (if too many CPU-bound processes) causing the I/O devices to go unused.

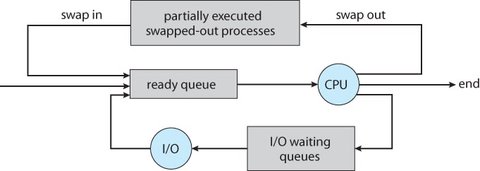

Medium-Term Scheduler:

In time-sharing systems (like UNIX and Windows), there may be an additional medium-term scheduler.

- Purpose of Medium-Term Scheduling:

- It is sometimes advantageous to remove processes from memory to reduce the level of multiprogramming.

- The process can later be reintroduced into memory and resume from where it left off. This is called swapping.

Swapping helps manage system load and memory usage, particularly when memory requirements exceed available resources.

3.2.3 Context Switch

A context switch occurs when an interrupt happens, and the system must save the current process’s state and load the state of another process to resume its execution.

Process of a Context Switch:

Context Saving:

- The OS saves the current process’s context (e.g., CPU registers, process state, and memory management information) in its Process Control Block (PCB).

Context Restore:

- The OS loads the saved context of the next process to execute, restoring its state (e.g., CPU registers, program counter).

Overhead: A context switch takes time and doesn’t perform useful work while switching, so adding overhead to the system.

Speed Variation: The time taken for a context switch can vary based on system factors, like memory speed and the number of registers involved.

Swapping vs. Context Switching

Swapping :

- Swapping is about managing memory by moving processes between RAM and disk. It’s done when the system runs out of memory or needs to adjust the number of processes in memory.

- The primary purpose of swapping is to manage memory and multiprogramming. It involves temporarily removing a process from main memory to free up space, and then later restoring it when needed. This is typically done when the system is overloaded or when the available memory is insufficient to handle all the running processes.

Context Switching :

- Context Switching is about switching the CPU’s focus between processes. It occurs frequently as the CPU moves between tasks, saving and restoring the state of processes.

- The purpose of context switching is to switch between processes during execution, so that the CPU can allocate time to multiple processes in a time-sharing environment. It is a fundamental operation in multitasking systems, enabling the CPU to switch between processes without having to halt the system completely.

Impact on the System

Swapping:

- Swapping is a high-cost operation in terms of time and resources because it involves transferring a process between main memory and disk. It is relatively slower than context switching due to the slower speed of disk compared to RAM.

- Involves main memory and disk. A process is moved from RAM to disk and back to RAM when it needs to resume execution.

Context Switching:

- Context switching is much faster than swapping, but still incurs overhead because the system has to save and load the process state (e.g., CPU registers, program counter, etc.) between switches. The overhead is minimal but significant when switching frequently.

- Involves CPU state (registers, program counter, etc.) but does not involve moving a process between memory and disk. The process remains in memory throughout the switch.