OS 8.02 - Virtual Memory, Page Replacement

Virtual Memory

Virtual memory is a technique that allows processes to execute even if they are not entirely loaded into memory. One of the major advantages of this scheme is that programs can be larger than the available physical memory.

Virtual memory abstracts the physical memory into a large, uniform array of storage, thereby separating the logical memory as viewed by the programmer from the physical memory. This separation provides an extremely large virtual memory to programmers, even when the system has only a smaller physical memory. As a result, programmers are freed from concerns about memory-storage limitations.

Moreover, virtual memory allows processes to share files and libraries, facilitates shared memory between processes, and provides an efficient mechanism for process creation.

A key benefit of virtual memory is that it enables one process to create a region of memory that it can share with another process. These processes treat the shared region as part of their virtual address space, but the physical memory pages that back this shared memory are actually shared between them.

Virtual Address Space vs. Physical Memory

The virtual address space of a process refers to the logical (or virtual) view of how a process is stored in memory. In this model, a process appears to begin at a certain logical address (often 0) and occupy a contiguous region of memory.

On the other hand, physical memory is organized into page frames, and the page frames allocated to a process may not be contiguous in physical memory.

Benefits of Virtual Memory

Executing a program that is only partially in memory brings many benefits:

A program is no longer constrained by the amount of physical memory available. Users can write programs that fit into an extremely large virtual address space, simplifying programming tasks.

Because each program can take up less physical memory, more programs can run simultaneously, increasing CPU utilization and throughput without increasing response time or turnaround time.

Less I/O is needed to load or swap portions of programs into memory, making each program run faster.

Demand Paging

In traditional systems, the entire executable program is loaded into memory from secondary storage before it begins execution. However, in many cases, we don’t need the entire program in memory at once.

A technique known as demand paging is used in virtual memory systems. With demand paging, pages of a program are loaded into memory only when they are actually needed during execution. Pages that are never accessed are never loaded into physical memory.

A demand-paging system is similar to a paging system with swapping.

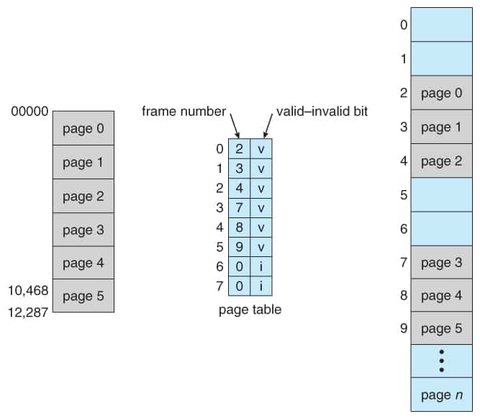

In a demand-paged system, while a process is executing, some pages will be in memory, and others will be in secondary storage. To track the location of each page, a valid-invalid bit scheme is used.

- When the bit is set to valid, the associated page is in memory.

- When the bit is set to invalid, the page is either not in the process’s address space or it is in secondary storage.

If a page is marked invalid and a process tries to access it, a page fault occurs. The page-table hardware, while translating the address, will detect the invalid bit and cause a trap to the operating system, indicating that the required page needs to be loaded into memory.

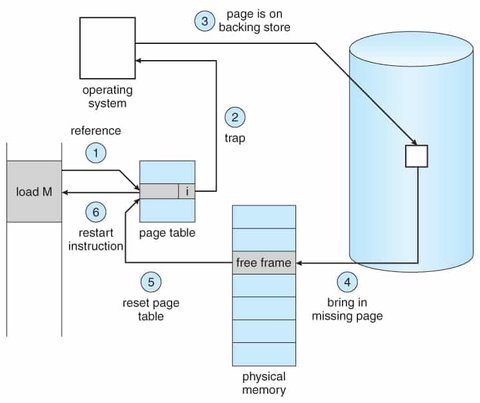

The procedure for handling a page fault is as follows:

- Check an internal table (usually maintained in the process control block) to determine whether the memory access is valid or invalid.

- If the reference is invalid, terminate the process. If valid but the page has not yet been brought into memory, load the page.

- Find a free memory frame (by taking one from the free-frame list).

- Schedule a secondary storage operation to read the desired page into the allocated frame.

- Once the read is complete, update the internal table and page table to indicate that the page is now in memory.

- Restart the instruction that caused the page fault. The process can now continue as if the page had always been in memory.

The hardware to support demand paging is similar to that for paging and swapping:

- Page table: Tracks whether a page is in memory or on secondary storage, with the ability to mark an entry invalid using a valid-invalid bit or special protection bits.

- Secondary memory: Holds pages that are not currently in main memory. This is usually a high-speed disk or non-volatile memory (NVM), often referred to as the swap device, with the storage area called swap space.

Page Replacement

When memory is over-allocated, page faults can occur. If a process requires a page that is not in memory, the operating system must find a free frame. However, if all frames are in use, the operating system must use a page replacement algorithm to select an existing page to replace.

The page-fault service routine, which includes page replacement, follows these steps:

- Determine the location of the desired page on secondary storage.

- Find a free frame:

- If a free frame is available, use it.

- If no free frame is available, select a victim page using a page-replacement algorithm.

- Write the victim page to secondary storage if necessary and update the page and frame tables.

- Load the desired page into the newly freed frame and update the page and frame tables.

- Resume the process from where the page fault occurred.

If no frames are free, two page transfers (one for writing the page out and one for reading the new page in) are required, effectively doubling the page-fault service time and increasing the overall access time.

Page replacement is a key feature of demand paging, completing the separation between logical and physical memory.

To implement demand paging, two critical problems must be addressed:

- Frame-allocation algorithm: Deciding how to allocate frames to processes.

- Page-replacement algorithm: Choosing which pages to replace when new pages need to be loaded.

Page Replacement Algorithms

Various page-replacement algorithms exist to determine which page to swap out when a page fault occurs. These include:

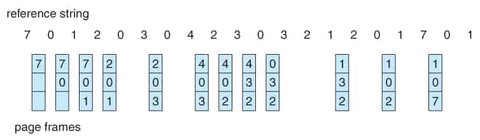

FIFO Page Replacement

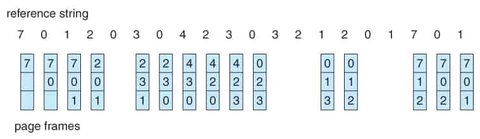

The simplest page-replacement algorithm is First-In-First-Out (FIFO). The FIFO algorithm associates each page with the time it was brought into memory. When a page must be replaced, the oldest page is selected.

Optimal Page Replacement

The optimal page-replacement algorithm selects the page that will not be used for the longest time in the future. This approach guarantees the lowest possible page-fault rate but requires knowledge of future page references, which makes it impractical for real-world systems. As such, it is typically used for comparison studies.

LRU Page Replacement

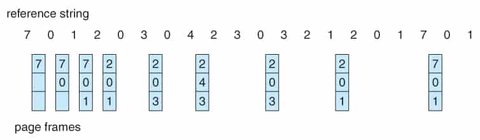

The Least Recently Used (LRU) algorithm approximates the optimal page-replacement strategy. It replaces the page that has not been used for the longest period of time, using past access patterns to predict future behavior.

LRU is widely used as a page-replacement algorithm and is considered to be effective.

Thrashing

Thrashing occurs when a process does not have enough frames to hold all the pages it needs, resulting in excessive page faults. When a process must constantly replace pages, it spends more time paging than executing, severely degrading performance. Thrashing results in high paging activity and leads to significant performance issues.

Unit Summary

Virtual memory abstracts physical memory into a large, uniform array of storage, providing benefits such as:

- Programs can be larger than the available physical memory.

- Programs do not need to be fully loaded into memory to execute.

- Processes can share memory.

- Processes can be created more efficiently.

Demand paging loads pages only when they are required during program execution. Pages that are not needed are never loaded into memory.

A page fault occurs when a page not currently in memory is accessed. The operating system then loads the page from secondary storage into an available page frame in memory.

Page replacement algorithms manage how memory is allocated when there is no free frame. Common algorithms include FIFO, Optimal, and LRU. Most systems use LRU-approximation algorithms due to the impracticality of implementing pure LRU.

Global page-replacement algorithms select pages from any process for replacement, while local page-replacement algorithms replace pages from the faulting process.