OS - Unit-2 - Synchronization Answered

Process Synchronization

Process synchronization refers to the coordination of the execution of processes that share resources, in order to maintain consistency and avoid conflicts.

A common issue that arises is race condition, which occurs when multiple processes concurrently access and modify shared data, leading to inconsistent, data corruption or incorrect results, depending on the timing of the operations.

Therefore, synchronization mechanisms are required to ensure correct process behavior and data integrity.

Critical Section Problem

- What is the critical section problem? Explain the requirements that must be satisfied by its solution.

- What are the requirements for providing a solution to the critical section problem? Explain.

Answer :

In a system with multiple processes (P0, P1, …, Pn−1), each process may include a segment of code called the critical section, where it accesses or modifies shared resources such as variables, files, or data structures.

The Critical Section Problem is to design a mechanism that ensures only one process can execute in its critical section at a time (no two processes execute their critical sections simultaneously), in order to avoid race conditions and ensure data consistency.

Each process follows a structure that typically consists of four sections:

- Entry Section – Code that requests permission to enter the critical section.

- Critical Section – Code that accesses shared resources.

- Exit Section – Code that signals the process has exited the critical section.

- Remainder Section – Code that executes when the process is not in the critical section.

Requirements for a Solution:

A valid solution to the critical-section problem must satisfy three essential conditions:

Mutual Exclusion : Only one process can be in its critical section at any given time. If one process is executing in its critical section, all other processes must be prevented from entering theirs.

Progress : If no process is currently in its critical section and there are one or more processes that wish to enter their critical sections, the selection of the next process to enter the critical section cannot be postponed indefinitely. Only processes that are not in their remainder sections should be involved in the decision.

Bounded Waiting : There must be a bound on the number of times other processes can enter their critical sections after a process has made a request to enter its critical section and before that request is granted. This condition ensures that no process has to wait indefinitely (prevents starvation).

These requirements ensure that the system maintains consistency, avoids deadlock, and allows fair access to shared resources among competing processes.

Interprocess Communication (IPC)

- What is IPC? Explain the two models of IPC.

- Explain IPC using message passing with an example.

- What is interprocess communication? Elaborate on the reasons for providing an environment that allows process cooperation.

- Elaborate on the benefits of interprocess communication. List the differences between direct communication and indirect communication.

- Is cooperation among processes necessary? Justify.

Answer :

Interprocess Communication (IPC) refers to the mechanism that allows processes to communicate and coordinate their actions when running concurrently. IPC is essential in systems where multiple processes must cooperate and share data.

Processes can be classified as:

Independent Processes: These do not share data or state with other processes and function without affecting or being affected by others. They operate in isolation and do not require synchronization with other processes.

Cooperating Processes: These share data with other processes and, therefore, require coordination and communication to ensure consistency and correct operation. IPC is required to enable cooperating processes to exchange information and synchronize execution.

Reasons for Process Cooperation

Providing an environment for process cooperation allows the operating system to support:

Information Sharing : Enables Processes to access and modify shared data between several users needing it.

Computation Speedup : Large tasks can be divided among multiple processes to run concurrently, improving overall performance by distributed workloads.

Modularity : Large systems can be broken into smaller, independent processes that are easier to manage and understand and maintain. IPC allow processes to collaborate without needing them to be tightly coupled.

Convenience : Cooperative multitasking allows users to run multiple applications at the same time, improving system usability and responsiveness.

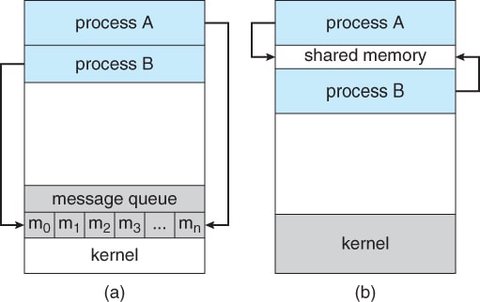

Models of Interprocess Communication

There are two primary models of IPC:

Shared Memory:

- In this model, cooperating processes communicate by accessing a shared region of memory, allowing for reading and writing data to this region.

- Synchronization mechanisms such as semaphores or mutexes are required to avoid race conditions when accessing shared memory.

Message Passing:

- Processes communicate by sending and receiving messages.

- This model is especially useful in distributed systems where processes may not share memory.

- Message passing is simpler for ensuring synchronization but can have higher communication overhead.

IPC Using Message Passing

Message passing allows processes to communicate and synchronize without sharing memory (same address space).

Message passing typically provides at least two operations by using system calls like send() and recieve():

send(message): Send a message to another process.receive(message): Receive a message from another process.

This approach is particularly helpful in distributed systems where processes run on separate machines connected by a network.

Producer-Consumer Problem Using Message Passing:

- The producer process generates data and sends it to the consumer process using the

send()operation. - The consumer waits to receive data using the

receive()operation. - If blocking (synchronous) communication is used, the producer may wait until the consumer is ready to receive the message.

Message Passing Implementation Models

Message passing systems can be implemented using different methods, including:

- Direct or Indirect Communication : Based on how processes identify each other.

- Synchronous or Asynchronous Communication : Defines whether the sender or receiver waits for acknowledgment.

- Automatic or Explicit Buffering : Relates to how messages are queued and managed.

Message Passing Communication

Direct Communication: Processes (Sender or Reciever) explicitly name each other during communication and messages are directly sent to process.

send(P, message)– Send message to process P.receive(Q, message)– Receive message from process Q.

Can be symmetric addressing (both sender and receiver know each other) or asymmetric addressing (only sender or receiver identifies the other).

send(P, message)- Send a message to process P.receive(id, message)- Receive a message from any process, withidset to the name of the sender.

Tends to create tighter coupling between processes, reducing flexibility.

Indirect Communication: Processes communicate via mailboxes or ports where messages are placed and retrieved, not directly with each other.

send(mailbox, message)– Send message to a mailbox.receive(mailbox, message)– Receive message from a mailbox.

Processes are more loosely coupled, offering more flexibility and scalability, especially in dynamic distributed systems spread across different machines.

Synchronous or Asynchronous Communication

Synchronous Communication (Blocking): The sender waits until the message is received. The receiver waits until a message is available. Suitable for situations where synchronization is required.

Asynchronous Communication (Non-blocking): The sender sends the message and continues without waiting for acknowledgement. The receiver checks for messages and continues execution.

Asynchronous communication is typically more efficient but requires additional mechanisms (like callback functions or notifications) to ensure proper synchronization.

In the Producer-Consumer problem:

- The producer sends a message using a blocking send and waits until the message is received by the consumer.

- The consumer receives a message via blocking receive, waiting until the message is available.

Buffering in Message Passing

Messages exchanged between processes are temporarily stored in queues known as message buffers. The buffering behavior depends how it is implemented in the system:

Zero-Capacity Buffer (No Buffering): No message is stored. Sender blocked and must wait for the receiver to be ready.

Bounded-Capacity Buffer: Buffer has a limited size. Sender must wait if the buffer is full. Consumer must wait if the buffer is empty.

Unbounded-Capacity Buffer: Theoretically infinite buffer. The sender never waits, but this is not practical for real systems.

Systems with bounded or unbounded queues are referred to as automatic buffering systems, while a system with a zero-capacity queue is referred to as no buffering.

Classic problems

Producer-Consumer Problem

One common problem in cooperative processes is the Producer-Consumer problem.

- Producer Process: Produces data and stores it in a shared buffer.

- Consumer Process: Consumes the data produced by the producer.

For both processes to run concurrently, they need a shared buffer — a region of memory where the producer can place data, and the consumer can retrieve it.

Synchronization between the producer and consumer is crucial to prevent problems like:

- Buffer Overflow : If the buffer is full and the producer tries to add more data, it may overwrite existing data before the consumer can consume it.

- Buffer Underflow : If the buffer is empty and the consumer tries to retrieve data, it may access non-existent data.

To avoid these issues, synchronization mechanisms such as mutexes, semaphores, or monitors are commonly used to ensure mutual exclusion and avoid race conditions.

Classic Problems Solutions

- What is a semaphore? Discuss the Dining Philosophers problem.

- Provide the solution for the Dining Philosophers problem using semaphores.

Answer :

A semaphore is an synchronization tool (integer variable) that manages access of multiple processes to a shared resource.

Apart from being initialized, the semaphore can only be accessed using two operations: wait() and signal(), both of which are atomic (indivisible) operations.

- The

wait()operation checks the value of the semaphore. If the value is greater than 0, it decrements the value and allows the process to proceed. If the value is 0 or less, the process will wait (i.e., it will keep checking the value until it can proceed). This prevents the process from proceeding if resources are unavailable.

wait(S)

{

while (S <= 0)

; // busy wait

S--;

}- The

signal()operation increments the semaphore value, signaling that a resource has been released or an event has occurred. This operation allows waiting processes to continue if necessary.

signal(S)

{

S++;

}Both the wait() and signal() operations modify the semaphore’s value. These operations must be executed atomically—meaning no other process can change the semaphore’s value while it’s being modified.

A binary semaphore is a special type of semaphore that can only have two values: 0 and 1. It is often used for mutual exclusion to ensure that only one process can access a critical section at a time.

A counting semaphore is a synchronization tool that can hold a non-negative integer value representing the number of available instances of a particular resource.

Dining-Philosophers Problem

Consider five philosophers who spend their lives thinking and eating. These philosophers share a circular table with five chairs, each belonging to one philosopher. In the center of the table is a bowl of rice, and five chopsticks are laid out for use.

Problem Setup:

- When a philosopher is thinking, she does not interact with her neighbors.

- From time to time, a philosopher gets hungry and tries to pick up the two chopsticks closest to her: one between her and the philosopher on her left, and the other between her and the philosopher on her right.

- A philosopher can only pick up one chopstick at a time. She cannot pick up a chopstick that is already in use by a neighboring philosopher.

- Once a philosopher has both chopsticks, she eats and does not release them until she is done.

- After eating, the philosopher puts down both chopsticks and returns to thinking.

This scenario is a simple model for the problem of allocating resources (chopsticks) among competing processes (philosophers) in a deadlock-free and starvation-free manner.

Challenges:

- Deadlock: If every philosopher picks up the fork on their left at the same time and waits for the right fork, no one can proceed.

- Starvation: A philosopher might wait indefinitely if others keep taking the forks they need.

- Concurrency Control : Philosophers must pick up and release chopsticks in a way that prevents conflicts and ensures progress.

Solution Using Semaphores

One straightforward solution involves representing each chopstick with a semaphore. The philosopher attempts to grab a chopstick by executing a wait() operation on the corresponding semaphore. When finished eating, she releases the chopsticks by executing the signal() operation on the respective semaphores.

Shared Data:

semaphore chopstick[5];

// Array of semaphores for chopsticks

- All elements of

chopstickare initialized to 1, representing that each chopstick is available.

Philosopher Process:

do {

wait(chopstick[i]);

// Pick up left chopstick

wait(chopstick[(i+1) % 5]);

// Pick up right chopstick

/* Eat for a while */

signal(chopstick[i]);

// Put down left chopstick

signal(chopstick[(i+1) % 5]);

// Put down right chopstick

/* Think for a while */

} while (true);- Each philosopher executes this loop, trying to pick up chopsticks, eat, and then think.